13/10/2024

During the summer, some people enjoy sunbathing at the beach, others hiking in the Alps. But, I’m a bit of a nerd, and I was curious about web-development… So here is the origin story of this website. With this post, I want to trace back my journey while building this website, explain what I learned, and how it relates to problems we encounter while doing research.

I wanted to build my personal website from scratch. What I mean by that is that I didn’t want to use site generators like Hugo or Jekyll with pre-defined templates. Not because they are bad, but because I wanted to do things by myself. Build something simple, have a bug, find where it comes from, increment, and so start to understand the basics of web-development.

The very first step was to choose a web framework, that is, a platform that handles the core functionality of the website so I can focus on the unique parts—the structure, the content and the look. I decided to go for Astro because it seemed easy to use, and well-documented. By going through their very nice tutorial, I had a minimal and ugly site running locally and deployed on GitHub Pages. Moreover, I learned to write simple HTML to add content to my webpages, and knew that I could use JavaScript to program interactive behaviour—like adding a counter that increments when the user clicks on it.

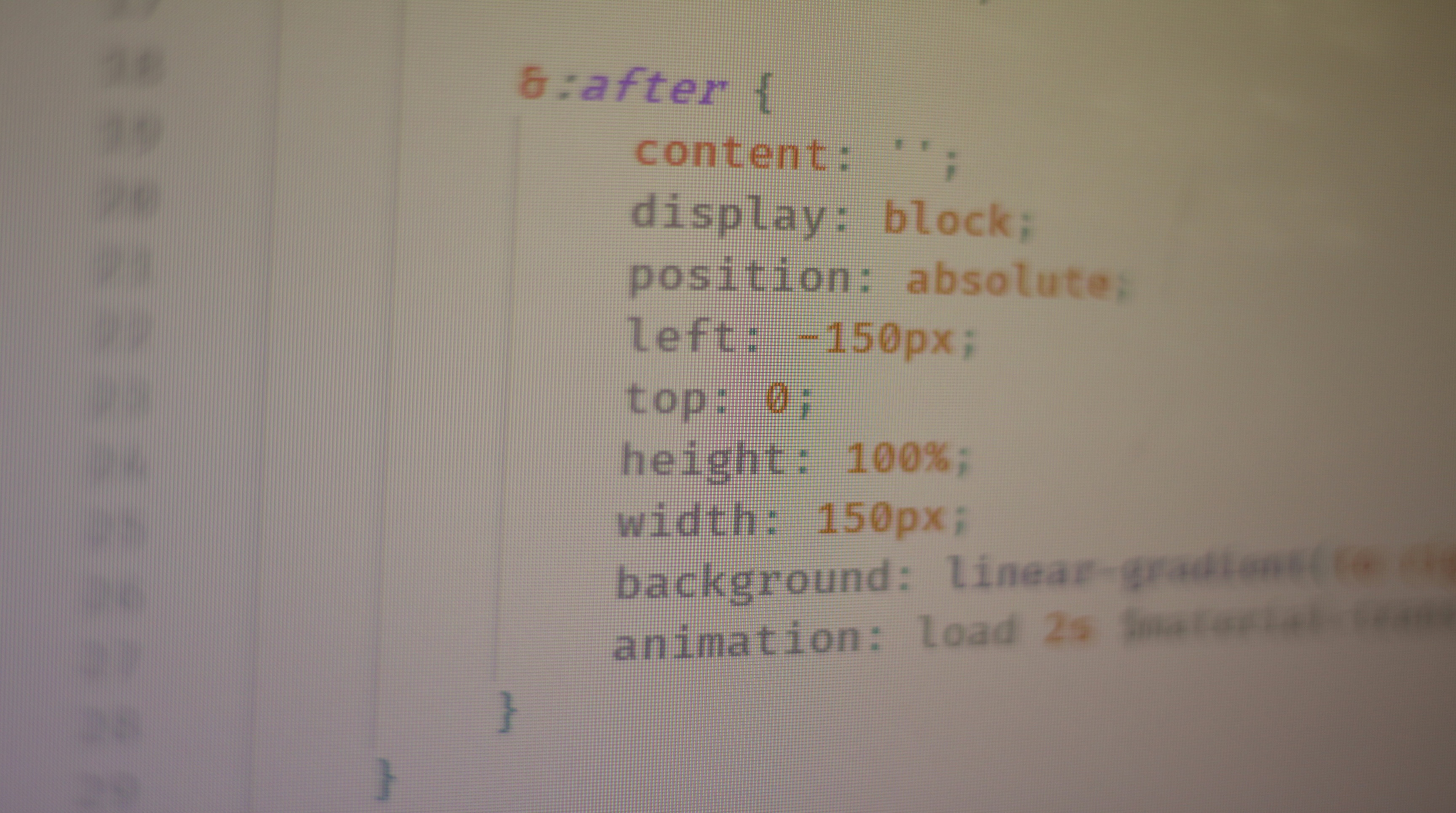

Next was to make the website less ugly, and so, to learn about CSS. It stands for Cascading Style Sheets and is the language used to style web pages. For example, if you want your titles to be in bold and red, this is done with CSS. This step took me more time than expected (as always). I wanted to have a look similar to the Takuya Matsuyama’s website. Yet, it meant to add things that were not trivial for me, like a sticky transparent navigation bar at the top of my pages. Or a home icon that smoothly animates when the user’s cursor goes over the home page button. But, after a lot of effort and some fruitful discussions with Chat (yes, I call Chat-GPT by its first name), I achieved something close to the look I liked.

Then, I have to say that I went too far. We always do, I believe. Without noticing, I was searching the web for obscure libraries that would make the content of my pages appear on scrolling, or to add cool transitions between my pages. If all of that looks very nice, I have to say now that it is pointless for what I want to do, that is, a simple personal website. I don’t need all this fancy stuff. I want something that just works, looks good, is easy to navigate—and more importantly—features interesting contents. And all the searching for this CoOL mOdErN and FaNcy transitions were just taking me away from adding relevant content to my website.

Thus, I went back to earth. I added a short description of myself, a research page to describe what I actually do for work, links to my socials, set-up my environment so I could feature nice code chunks and equations in my posts, and started to think about blog posts that I could write. I’m still figuring this out, and this post is my first attempt.

In the end, I think that what I truly learn—rather than the basics of web-development—is to be radically simple. When we progress in anything, we quickly become able to do com.pl.e.x t.h.ings—especially when powerful tools are our disposal. Yet, more often than we think, problems we face implies a simple solution. And by not choosing the simple solution, we end up losing time both because complex solutions are more difficult to implement at first, and very time-consuming to manage in the long run.

I believe that although this applies particularly well to programming, it could also be relevant for research. We may sometimes have the wrong tendency to use overcomplicated—and therefore inadequate—tools to solve our problems, either because they are tReNdY, we have high amount of computing resources available, or there is a new library that allows us to run a complicated models in few lines of code (I know about that, I wrote one). However, in research this use of tools—when not suited for the problem tackled—doesn’t only cost time, it also costs clarity. And this is much worse. Science should seek clarity, not add layers of complexity on already complex problems.

I feel that this goes back to the concluding sentences of Robert May on the Uses and Abuses of Mathematics in Biology:

Perhaps most common among abuses, and not always easy to recognize, are situations where mathematical models are constructed with an excruciating abundance of detail in some aspects, whilst other important facets of the problem are misty or a vital parameter is uncertain to within, at best, an order of magnitude. It makes no sense to convey a beguiling sense of “reality” with irrelevant detail, when other equally important factors can only be guessed at. Above all, remember Einstein’s dictum: ‘models should be as simple as possible, but not more so.’